Overview

Eating disorders are serious, often life-threatening mental health disorders conditions characterised by behaviours around food, eating, weight, shape, and exercise which negatively affect a person’s health and wellbeing in just about every domain. It is important to note that eating disorders are not solely caused by concerns pertaining to weight, shape, and body image but rather a range of factors that come together and intertwine in complex ways – many of which modern psychology still is yet to understand.

It is also important to recognize the significant overrepresentation of eating disorders among neurodivergent individuals. Neurodiversity includes conditions such as Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), ADHD, dyscalculia, dyslexia, and tic disorders for example. The ability to “mask” can make it harder to recognise early signs of an eating condition.

For more on the link between neurodiversity and eating disorders, see Eating Disorders Neurodiversity Australia.

Did You Know:

Only 6% of people who experience eating disorders are medically classified as ‘underweight’ (in accordance with BMI)

Eating disorders are not isolated to women and girls

Eating disorders can occur at any age

Anorexia Nervosa is NOT the most common type of eating disorder

Anorexia Nervosa has the highest mortality rate out of any psychiatric disorder

It is very rare that eating disorders occur in isolation

Video: Talking about eating disorders helps; Butterfly Foundation

Eating vs Feeding Disorders

Many people are unaware that there is a difference between feeding disorders and eating disorders, and often at times it can be hard to determine if someone is experiencing a feeding disorder or an eating disorder.

Both feeding and eating disorders are characterised by a disordered relationship with food and (often, not always) disruption to a person’s ability to adequately and appropriately nourish themselves. However, feeding disorders – which are more common in children and infants – are more a direct result of food intolerances whilst eating disorders are complex mental health concerns affecting both mental and physical health.

Many clinicians also believe that there is a connection between feeding disorders in childhood and eating disorders later in life, though there is little research to support this.

This page primarily talks about eating disorders, however will give a brief overview of some common feeding disorders including rumination disorder and pica.

Types of Eating & Feeding Disorders

There are various different types of eating disorders, despite what the media may represent. Stereotypical representations often focus around Anorexia Nervosa or Bulimia Nervosa (though these depictions in themselves are highly sensationalised). Other types include Binge Eating Disorder, Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID), PICA, Rumination Disorder, Other Specified Feeding and Eating Disorder,

Anorexia Nervosa

Anorexia is a restrictive eating disorder in which a person’s mind does not allow them to eat freely and in accordance with their body’s needs. It is stereotypically depicted as a very thin, emaciated female refusing to eat, however this is an extreme and a sensationalised story. In most cases, anorexia does not look like this.

Some common characteristics of anorexia include:

- Intense fear of gaining weight

- Excessive and/ or compulsive exercise (including lower-level movement compulsions)

- Fear of ‘losing control’ around food

- Strong feelings of guilt or shame when eating or in relation to specific foods that society may deem to be ‘unhealthy’

- Inability to be spontaneous, especially when food is involved

- Hyperfocus on food

- Constant thoughts about eating – for instance a person might finish one eating occasion and be instantly thinking about the next. This is what is referred to as ‘mental hunger’

- Desire to feed other people but often with an inability to eat the same food themselves – for some this might look like a sudden interest in baking or cooking

- Constant exhaustion that cannot be resolved by sleeping

- Rapid or sudden changes in a person’s weight

- Laxative abuse

- Loss of menstrual period for some however others may never lose their period. This doesn’t determine severity in any way

- Hiding food or hoarding food

- Low bone density – after an extended period of restriction, loss of bine density can lead to osteoporosis or osteopenia

It is so important to note that food restriction does not always amount to weight loss.

Bulimia Nervosa

A serious and life-threatening eating disorder characterised by events of binge-eating followed by attempts to reduce or avoid weight gain, referred to as ‘compensatory behaviours’

People with bulimia are typically considered to be in a ‘normal’ weight range – that is; their BMI falls within what is typically considered to be ‘healthy’.

Some examples of compensatory behaviours include:

- Excessive or compulsive exercise

- Using and misusing laxatives

- Vomiting after eating

- Restriction of food intake

- Misuse of water pills (diuretics)

It is important to note that the fact that a person’s weight is not considered to be concerningly low does not mean that they are not unwell or that they are not at risk of serious medical complications. When food intake is restricted, a person is at risk of experiencing the physical complications of malnutrition regardless of the size of their body. Especially if a person is engaging in purging behaviours or excessive exercise behaviours, the effects on the body can be even more significant.

Binge Eating Disorder (BED)

Binge Eating Disorder, is a serious mental health condition where a person engages in recurrent periods of bingeing.

In a binge, a person consumes an amount of food that would typically be considered large in one sitting, usually over a very short period of time.

There is a difference between bingeing (loss of control and inhibition around food – eating to combat or soothe an emotion, fear, or even boredom) and overeating (eating past fullness, something that we might tend to do if we are enjoying ourselves at a celebration)

Orthorexia

Orthorexia is characterised by an obsessive preoccupation with ‘clean eating’ or following a ‘healthy’ diet.

Orthorexia often looks very similar to other eating disorders – especially anorexia nervosa – and often co-exists.

Note: Orthorexia is not yet classified as a formal eating disorder diagnosis.

Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder

Avoidant restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) is often misunderstood as being ‘picky eating’, unfortunately it is far more complicated than this and it is by no means what is typical childhood ‘fussiness’.

People with ARFID have challenges relating to the taste, texture, smell, colour, and unfamiliarity of certain foods. They typically have an aversion to food, with no real interest in it or in eating, which can lead to nutritional intake, which is inadequate or heavily limited, thus resulting in similar physical complications as those seen in anorexia nervosa. For this reason, it can be incredibly difficult to differentiate.

Pica

Pica mainly affects people who are pregnant and children. It is a feeding disorder characterised by the persistent eating of non-food substances or objects that are not normally intended to be consumed – such as ashes, dirt, clay, or even flaking paint.

The main medical risks posed by pica are dependent on the substance that the person is consuming – but may include lead poisoning, intestinal damage, damage to teeth, infections, bowel problems, stomach pain, and blood in the stool.

For children, it is normal and expected that they will put things in their mouths that are not intended for consumption. Perhaps they put objects in their mouth, bite their fingernails, or chew on hair and toys. However, pica is more a compulsive need to consume non-food items

It can be very difficult to detect – especially as many people will hide these behaviours – and often is not done so until medical complications arise.

Other Specified Feeding and Eating Disorder (OSFED)

Other Specified Feeding and Eating Disorder (OSFED) typically refer to eating disorders that display similar symptoms to other identified eating disorders that do not necessarily meet the conditions for diagnosis. It is used to denote that an eating disorder is present and that it is causing intense distress or challenges in a person’s life.

Rumination Disorder

A feeding condition in which a person repeatedly regurgitates undigested food or partially digested food. They spit up food, and then either re-swallow it or spits it out. This regurgitation is a reflex – it is not intentional or purposeful.

It is important to note that a person with rumination disorder is not spitting up food because they feel nauseous or unwell.

Diabulimia

Diabulimia is not recognised formally in the DSM-5.

It is a life-threatening condition where a person living with type-1 diabetes intentionally give themselves less insulin (or stop taking it altogether) with the intention of deliberate weight loss.

The DSM-5 classes anorexia nervosa separately from ‘atypical’ anorexia (i.e. that which occurs in a person whose BMI is not considered to be ‘underweight’.

It is important to recognise that a person can be experiencing anorexia at any weight.

Only a small minority of people with eating disorders are actually classified as being ‘underweight’

It is also important to note that nutritional restriction is incredibly dangerous regardless of a person’s body weight or size.

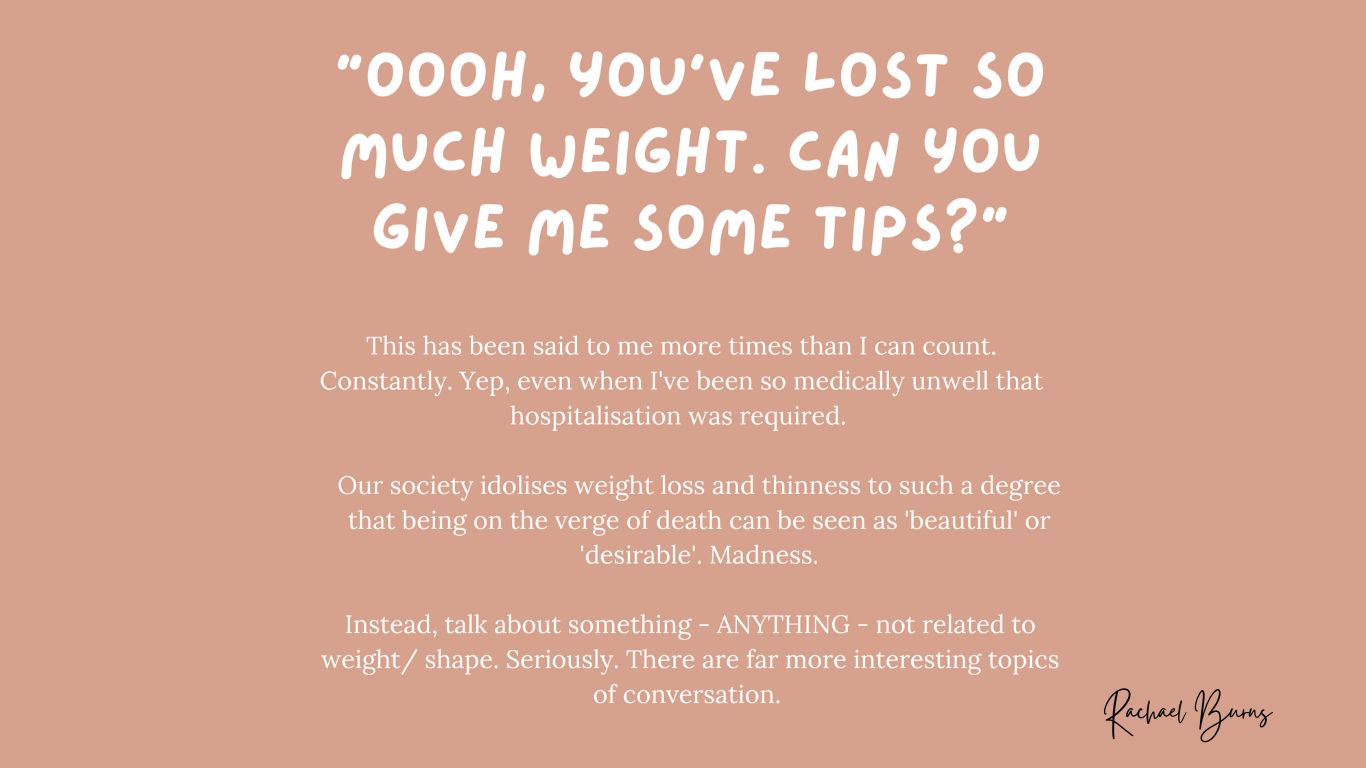

Video: Why Would I Choose This by Rachael Burns; REELise

Eating Disorders and Body Image

Eating disorders are often portrayed as an obsession with mirrors and celebrities, but body image is just one of many contributing factors. Some disorders, like ARFID, are unrelated to appearance. However, body dysmorphia can deeply impact self-perception and self-worth—it is not about vanity but a health condition.

Body image concerns fluctuate; some struggle most when unwell, while others deteriorate over time. These concerns are personal and not the only factor at play.

Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD)

Body Dysmorphic Disorder involves feelings of shame, guilt, or disgust about one’s appearance. Unlike common misconceptions, it is not about vanity but an obsessive condition that disrupts daily life.

Body Dysmorphia vs. Body Dissatisfaction

Feeling self-conscious is common, but body dissatisfaction differs from Body Dysmorphia. Dissatisfaction involves insecurities, whereas Body Dysmorphia is an intense, obsessive fear of perceived flaws that impacts well-being.

The Link Between Body Dysmorphia and Eating Disorders

Body Dysmorphia and eating disorders often co-exist but are not the same. Body Dysmorphia can focus on any aspect of appearance, not just weight. Likewise, not everyone with an eating disorder experiences Body Dysmorphia.

Eating Disorders and Mental Health

According to Eating Disorders Families Australia (EDFA), it is estimated that between 55-97% of people experiencing an eating disorder will also experience a co-occurring mental health condition such as PTSD or OCD.

These co-existing mental health conditions may emerge before, during, or after an eating disorder, sometimes masked by the illness.

Eating Disorders as Coping Mechanisms

Eating disorders provide temporary emotional relief but are harmful in the long run. Recovery isn’t just about stopping behaviours—it requires replacing them with healthier coping strategies for lasting well-being.

Myths

MYTH - eating disorders only affect teenage girls

FACT – eating disorders can affect anyone, regardless of gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, social class, religion… or any other demographic.

Myth - anorexia is the most serious eating disorder

Fact – whilst anorexia has the highest mortality rate out of any psychiatric condition, all eating disorders can be incredibly life threatening, regardless of a person’s weight

Myth - people with anorexia are scarily thin

Fact – you cannot tell is someone has anorexia merely by looking at them. The depiction of anorexia that is showcased in the media is only one of its many presentations, and is certainly not the most common.

Myth - people with anorexia don’t eat

Fact – in most cases, people with anorexia do eat. In a lot of cases, they might even eat more (by volume) than what people without eating disorders do, and in order to recover from a restrictive eating disorder like anorexia they most certainly need to eat more than people without an eating disorder. The amount of food a person does eat or doesn’t eat does not mean that they are ‘better’.

It is not uncommon for people with eating disorders to either mainly eat in front of an ‘audience’ or to mainly eat alone.

People with eating disorders are not immune to starvation, and even in the very rare case that a person is refusing oral intake entirely, they still require nutrition (which would most likely be given in a clinical setting through a nasogastric feed).

Myth - people with eating disorders hate food

Fact – most people with eating disorders actually quite like food, in fact very often they are incredibly obsessed with it and centre it in any way possible. It is not uncommon for people with eating disorders to have a constant desire to feed others, to watch cooking shows, to look through cookbooks etc. It is – generally – not so much about not liking food as it is about not liking the way it makes them feel. Fear around food is typically because of the nutritional content and the ways this may change a person’s body or lead to a perceived lack of control as opposed to the actual act of eating.

The exception to this is Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID), in which a person usually has very little interest in food and may fear eating not because of the nutritional content, but because of a fear of choking, vomiting, or being harmed.

Myth - only women have eating disorders

Fact – eating disorders affect people of any and all genders and gender identities.

Myth - eating disorders are a choice

Fact – an eating disorder is not at all a choice. Eating disorders typically have an initial trigger of weight loss, which we know can happen for a number of reasons, after which genetics, environmental factors, personality type, stressors and an endless list of factors have far more of a role in its development and maintenance than choice ever had or will have.

For more myths and facts, see Eating Disorders: Myths and Facts written by Lived Experience advocate Rachael Burns.

Signs and symptoms

there are no universal rules defining how a person’s eating disorder may present, and people rarely if ever display every single one of the possible signs.

That said, there are warning signs that may indicate a person is struggling with disordered eating (a precursor to eating disorders) or an eating disorder.

Common symptoms of anorexia

- Rapid changes in a person’s weight (gain or loss).

- Sudden peak in interest or obsession around food.

- Feeling a desire to always ‘feed’ others but not eat its oneself

- Difficulty concentrating, absence of mind and struggling to hold a conversation.

- Fatigue, malaise and overall exhaustion.

- Irritability or changes to a person’s personality

- Inability to be flexible or spontaneous, especially when food is involved

- Compulsive and/ or excessive exercise behaviours (including lower-level movement), typically accompanied by guilt if this routine is broken

- Eating in secret or alone

- Being inflexible when food is involved and being unable to act spontaneously.

- Repetition of the same foods over and over, to a point that variety becomes very limited.

- Significant and consistent changes to a person’s eating habits

- Social withdrawal and isolation

- Not wanting to participate in events is food is involved

Causes of eating disorders

Eating disorders are complex conditions that are a result of numerous factors all uniting in a ‘perfect storm’. There is no one singular cause of eating disorders, and not every potential cause is a part of everyone’s experience. It is highly individual and often will never be completely determined (nor does it necessarily need to be).

Some factors that CAN contribute to the development of an eating disorder include:

- Genetic predisposition. Many talk about it as though the genes ‘lay the foundation’ whilst the external factors ‘build the structure’ in relation to the development of an eating disorder. This theory is supported by the fact that

- Academic ‘giftedness’ and academic pressure

- Co-occurring mental health conditions

- Neurodivergence

- The influence and strength of diet culture in a person’s life

- Body dissatisfaction and body image issues

- History of dieting

- Poor self-esteem and self confidence

Risk Factors

Eating disorders are not caused by any one thing in particular. There are so many complex and intersecting experiences and factors that may lead a person to develop an eating disorder, many of which also have nothing to do with body image concerns.

Some risk factors include:

- Genetic predisposition (I.e. there being a family history of eating disorders)

- Neurodevelopmental challenges and neurodivergence (autism, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder).

- Co-occurring mental health challenges

- History of dieting or a culture where dieting is commonly encouraged

- Perfectionism and exceptionally high self-standards

- Cognitive inflexibility and rigidity

- Impulsivity

- Body image concerns and body dissatisfaction

- History with another mental health challenge

- Addictive personality or history of addiction

- Being surrounded or deeply immersed in diet culture

- Minority stress

- Acculturation

- History of trauma

How are eating disorders diagnosed?

Eating disorders in Australia are diagnosed by doctors or mental health professionals, typically through multiple assessments based on the DSM-5. General practitioners (GPs) are often the first point of contact and should be able to identify and initiate management. However, diagnosing and treating eating disorders can be difficult for a number of reasons.

Many diagnostic tools, like the SCOFF assessment, focus heavily on weight and shape, which can at times influence the outcome in those who don’t fit the stereotype. Additionally, significant physical health impacts can occur without visible signs. For example, a person may have a normal BMI but dangerously low potassium from purging.

One indicator of physical health impact, separate from weight and BMI, is postural orthostatic tachycardia (excluding those with POTS).

Common Treatments

There are various treatment options available for someone experiencing an eating disorder, and the most suitable approach depends on the person’s unique needs and the specific condition being treated. Recovery is not one-size-fits-all, and treatment plans often involve a combination of medical, psychological, and nutritional support.

Below is a list of common treatments, though it is not exhaustive

Family-Based Therapy

Family based therapy is a common treatment used for young people with an eating disorder who still live at home with their family.

It is based on the fundamental premises that:

- Nobody is to blame for the development of the eating disorder (unlike in family focused therapy )

- It externalises the eating disorder as a separate being

- The young person does not have to consent to treatment

- Hospitalisation is a short-term solution

- The cause of the illness does not matter.

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT)

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) is a type of psychotherapy (talk therapy) that encourages people to change their thoughts, feelings and behaviours. CBT is typically conducted one-on-one and will involve talking to a psychologist. It is important to note that for adolescents, this process will involve the family.

Dialectical Behavioural Therapy (DBT)

Dialectical Behavioural therapy (also called DBT) is a type of psychotherapy that provides a structured approach to building practical life skills.

DBT is usually delivered through a combination of group work, individual work, and homework.

Radically Open Dialectical Behavioural Therapy (RO-DBT)

Radically Open Dialectical Behavioural Therapy (RO-DBT) is just that – ‘radical’. It is a stream of DBT specially tailored for individuals who experience intense over-control and who may be resistant to many more traditional treatments.

Responsive feeding therapy (RFT)

Responsive feeding therapy is considered an effective treatment for Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID) amongst young children, in which carers create a pleasant and distraction-free space around meals. They model a healthy relationship with food and aim to create a safe environment around foods.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT)

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) is a type of therapy that uses proven methods to help people make changes to their behaviour. It combines acceptance and mindfulness, being aware of the present moment, with commitment and behaviour change techniques.

ACT for eating disorders focuses around helping people to accept and sit with uncomfortable feelings whilst committing to behaviours that are in line with their life goals and values.

Exposure and Response Prevention therapy

Exposure and response prevention therapy allow a person to gradually face their fears in a safe and controlled environment, allowing them to rewire neural pathways associated with fear, danger and avoidance.

Dietetics

A key part of recovery from most eating disorders is nutritional restoration, and in all eating disorders it can be incredibly beneficial to work with a dietitian to create a customised meal plan in line with what a person needs to adequately nourish their body.

Help, Support & Next Steps

Supporting someone with a suspected eating disorder starts with listening, showing understanding, and believing them when they say they’re struggling. Be patient, keep an open mind, and offer a safe space for them to talk without fear of judgment.

Eating disorders can be difficult to talk about, and some individuals may not even realize they have one. It’s okay not to have all the answers—that’s the role of health professionals. A GP, clinical psychologist, or dietitian is a good starting point for assessment and guidance. They can help develop a treatment plan and connect the person to appropriate services.

Encouraging someone to see a GP can be a helpful step. You might say:

“How about we visit a GP just to check in? I’m worried about you. I can come with you and wait outside if that helps. You don’t have to tell me anything unless you want to.”

Some people may feel more comfortable speaking to a professional before opening up to loved ones, and that’s okay. The important thing is to be there for them when they’re ready.

If you or your loved one experience severe medical symptoms, seek immediate assistance by calling 000. Hypoglycemia (low blood sugar) and other physical complications of eating disorders can be life-threatening, leading to seizures, coma, organ damage, or even death if untreated.

It’s essential that health professionals conduct thorough assessments, as serious medical complications can occur at any BMI. Comprehensive evaluations beyond weight alone are crucial to ensuring proper care and intervention.

Websites

Butterfly Foundation

Offers support for eating disorders and body image issues. Options include calling their National Helpline on 1800 33 4673, chatting online, joining a support group, or reaching out via email Visit site(Opens in a new tab)

Butterfly Foundation: Find a Professional

The directory lists a range of practitioners and services that can be helpful, although a GP is also a good place to start if you’re unsure. Visit site(Opens in a new tab)

Eating Disorders Families Australia

Offers support, mentoring, advice and community to help people with eating disorders on their recovery journey Visit site(Opens in a new tab)

Inside Out Institute for Eating Disorders

Australia’s national eating disorder research and clinical excellence institute. Visit site(Opens in a new tab)

Eating Disorders Victoria

Offers guidance and support to help Victorians understand and recover from eating disorders. At every stage, from discovery to recovery. Visit site(Opens in a new tab)