‘Person’ before ‘patient’.

At Finding North, we acknowledge that personal perspectives are valuable and that each person’s experience may be different. We thank all of our contributors who continue to share their insights with us.

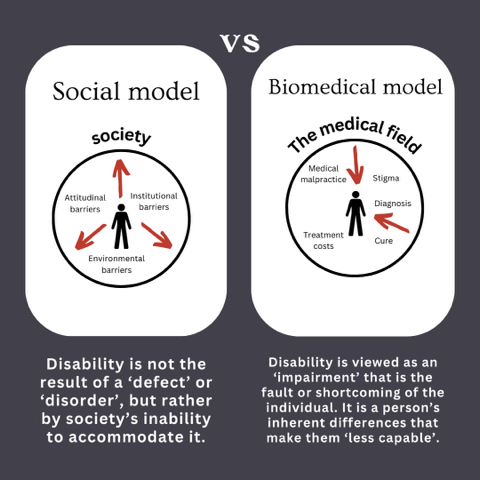

This piece has been written from a lived experience perspective and explores different models of health, specifically the biomedical model and the biopsychosocial model. These are distinct from the models of disability – the charity, medical, social, and human rights models.

Health is an arbitrary concept

No two people experience health in the same way and likely will view it through different lenses, influenced by the endlessly complex environment in which they exist.

To some, maybe it’s merely a state of physical fitness. To others, perhaps it more heavily leans into emotional and psychological wellbeing. To me, ‘health’ is a combination of various elements which vary depending on the unique and endlessly complex components that make up the human condition.

Despite the fact that there will never be one universal definition, there are still fundamental systems and models which try to find one. The biopsychosocial model, the biomedical model, the religious model, the ecological model, the psychosomatic model, and the social-emotional wellbeing model are each examples of this. If you are unfamiliar, I highly recommend you check them all out.

Each has merit in different contexts, however one in particular is favoured by our current system.

Humans like to sort things into neat portfolios of logic that can be filed away in the library that is their mind. It’s in our nature to seek meaning and sense even in things that cannot be understood. In the rigidly structural world in which we live, it’s only natural that our healthcare system operates biomedically.

The biomedical model forms the basis of modern-day healthcare. It works in organised systems off of pre-determined diagnostic criteria, checklists, labels and prescriptive cures. It is more often than not that when we go to the doctors, we will leave with a script that can be used to grab some pills that we are told will cure one or all of our symptoms.

As a result, there is still an overwhelming perception of health as being a state of physical fitness and the lack of disease or ‘ailment’ as opposed to something layered and complex.

The biomedical model looks at illness as a ‘flaw’ that needs to be remedied. It defines illness on the basis of systematic assessment, in which ‘symptoms’ deviate from what is ‘expected’ or ‘normal’. It posits that illness is resultant of a physical cause – in relation to mental health, this being ‘atypical’ neurotransmitter activity. Essentially, it assumes that mental ill-health is related only to biological causes which can be identified/ diagnosed, monitored, changed, and treated.

Perhaps this model is great when there is an identifiable cause and a simple treatment. For many physical illnesses, perhaps it is sufficient. However, when it comes to mental health and mental ill-health, this is not typically the case and as such this model certainly has limitations.

A medical model of mental health care is created for neurotypical, non-disabled individuals who think and feel within a narrow margin of ‘normality’. It minimises a ‘patient’ and fails to address the numerous complex interactions between domains that unite to create someone who thinks and feels and loves and hurts. A person.

Conversely, the biopsychosocial model recognises that biology is one of many factors that contributes to a person’s level of health and ability. It assumes that health is a state of mental and physical well-being, which is influenced by biological factors, social factors, and psychological factors interacting. It explains that when one factor is affected, the others will inadvertently also be impacted as they are inherently interlinked.

Even though this model exists, there are still shortcomings in it and in practitioners’ ability to abide by it in a highly biomedical world. Unfortunately, it often still fails to cater to those who don’t think and operate neurotypically.

This said, there is no disputing the fact that a number of more traditional approaches to therapy based on the biopsychosocial model have shown efficacy under the right conditions. For this reason they are usually the first approach.

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) is a type of talk therapy that is used to shift unhelpful ways of thinking common in anxiety disorders, mood disorders, trauma related disorders, eating disorders and substance abuse disorders. It is the ‘gold standard’ of practice in the psychotherapy field. It is an ‘umbrella term’ which encompasses a number of psychotherapeutic techniques focusing on thoughts and behaviours. CBT follows the principle that thoughts impact feelings, and feelings govern behaviour. It aims to find alternatives to ‘unhelpful’ patterns of thinking.

Dialectical Behavioural Therapy (DBT) is another form of talk therapy used commonly in the treatment of people who experience intense emotions such as those seen in borderline personality disorder, eating disorders, post-traumatic stress disorders, anxiety disorders, mood disorders and substance abuse disorders. DBT is a branch of CBT which works by accepting and harnessing contradictory concepts of change and acceptance – it encourages a person to take themselves just as they are whilst also embracing fluidity. It promotes mindfulness, sitting with emotion, acknowledgement, and openness to multiple truths.

As someone with lived experience of an eating disorder in my youth, I am mostly familiar with the practice that is family based therapy.

Family-based Therapy (FBT), also known as the Maudsley Method, is specifically designed for treating restrictive eating disorders. It is the most common and efficacious therapy for anorexia nervosa amongst adolescents and children living at home with family. It has also been used more recently for treating bulimia nervosa. It utilises a family unit to renourish a child – whereby parents/ caregivers have a responsibility to monitor, manage and ‘police’ eating. It requires the young person to (often unwillingly) relinquish control and autonomy.

I encourage you to take a look into my work around family based therapy outlining its strengths and it’s weaknesses. Whilst it is often the go-to approach, it can also be harmful when used as a band-aid solution.

It is also essential to understand the difference between FAMILY therapy and FAMILY-BASED therapy, as they are both entirely different concepts. Whilst family therapy focuses more so on a structured and professional approach to navigating family conflict. It is about navigating problems, communication challenges and creating synchronicity within a family unit. Comparatively, family-based therapy is about using the family as a tool to support long-term and sustained recovery in young people with an eating disorder. It is not viewing a family as the problem but rather mobilising them to re-nourish a young person as opposed to handing autonomy to the person receiving care themselves.

Traditional therapies absolutely have a time and a place, but they are not and should not be the only approach.

I am very much of the mindset that therapy can benefit anyone – regardless of if they have a diagnosable ‘disorder’. That said, the wrong therapy can cause a great deal of damage, and this fact is often much overlooked. Iatrogenic harm refers to harm caused as a result of medical or psychiatric treatment, whether or not it is intended.

Doctors are sworn to the oath of ‘do no harm’, though the truth is that even with all the best intentions this is still largely unrealistic. Especially when it comes to mental health, what may be helpful for one person may be detrimental to another. It may exacerbate existing trauma, create resistance, and leave an individual feeling that they are the problem.

Traditional therapies are very much geared towards neurotypical patients, meaning that for many people who do not ascribe to a neurotypical pattern of thinking, feeling and behaving, there are often many cracks for them to inevitably fall through.

Neurodivergence is an umbrella term that refers to ways of thinking and feeling that deviate from what is considered normative. Though perhaps most well know in reference to Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), neurodivergence more broadly includes a range of different neurological patterns characteristic to Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), anxiety, dyscalculia, dyslexia, tic disorders and a host of other so-called ‘disorders’.

There is significant clinical evidence that whilst some neurodivergent folk will benefit from traditional therapies, there is also a considerable percentage that will not, or whom will not experience benefits in the same way that neurotypical people may.

In my own experience, many of these therapies have actually inflicted harm. Instead of being helped in the ways that I needed, I was made to feel like a failure for the fact that I was ‘unresponsive’ to them and that in many instances they actually made my mental health worse.

Being founded on ableism, many therapies try to hide and erase traits of neurodivergence such that others can feel more comfortable around them. It fails to recognise that some peoples’ brains are wired differently and will experience and express emotion in ways that are not considered ‘normal’.

Neuro-affirming practice should acknowledge and accept neurodivergent traits without pressuring individuals to mask them. Where other therapies may focus on overcoming what it perceives as ‘impairments’, those that are neuro-affirming and neurodiversity-informed instead encourage acceptance, reframing, and self-advocacy. It’s also important to note that this is not something that can be sufficiently covered in one training course that gives an end certification. Neuro-affirming practice is a constant commitment to adapt neurotypical therapies for neurodivergent brains, to learn, and to embrace differences.

There are multiple ways in which a practitioner can make therapy more suitable for neurodivergent people. In some instances, this may be as simple as shifting away from the idea that a neurodivergent person needs to be ‘fixed’ or moving away from the focus on naming and labelling emotions.

There are also a number of ‘alternative’ therapies that may be more appropriate for neurodivergent folk. folk. A lot of the traditional therapies as mentioned above also have shown potential to be tailored such that they are more neuro-affirming – perhaps they don’t ask a person to name their emotions, create a sensory-friendly space, avoid using inference or are accommodating of peoples’ avoidance of eye contact.

As far as new therapies go, a new(ish) branch of DBT, called Radically Open DBT – or RO-DBT – has the potential to be far more effective than traditional models of DBT or CBT, which are more focused on neurodivergence as an ‘impairment’ that needs ‘fixing’.

If you observe a child for long enough, you might notice that they have a tendency to think in black and white. What this means is that they usually perceive a situation or experience as either one thing or the other, but rarely in the grey space that exists in between.

For neurodivergent people, this way of thinking is natural not just in childhood but into adolescence and adulthood. This might present as an incredibly strong sense of morality and a powerful conviction of right from wrong. It is not an inherently bad thing, but it can certainly make it more difficult to benefit from typical approaches.

It is also important to note that black and white thinking is not specific to neurodivergence, rather is a trait often correlated with over-control, routine, perfectionism, change avoidance, fear of failure, high personal standards and structure. In many situations, it is also a completely normal, human behaviour.

RO-DBT is specifically designed for people with a tendency to think in this manner. It focuses on enhancing social connectedness based on the concept of ‘radical openness’, which goes beyond mindful awareness and into willingness to seek uncertainty and discomfort. This helps people develop emotional flexibility and carry curiosity.

As a highly creative person, my experience with RO-DBT has also intertwined with art therapy. Being highly critical of my own work, it has been incredibly interesting (and also fun) to experiment with creating and accepting intentionally ‘bad’ pieces and challenging what this means.

Temperament-based therapy with supports (TBT-S) is another emerging treatment that shows promise for neurodivergent people. What I love about it is that it aligns with social perspectives that what we refer to as ‘illness’ is not always a ‘problem’ and does not always need ‘fixing’. Whilst it still looks at behaviour change as the end result, it does so by embracing and redirecting one’s inherent personality traits. It does not label parts of one’s character as ‘bad’, instead it looks at how parts of someone’s personality that may be harming them can instead be harnessed in ways that instead help them.

For humans as a whole and even more so for those who are neurodivergent, it is integral that treating mental ill-health or poor mental health (because there is a difference) is done in an integrative manner.

This means moving away from purely a biomedical model of diagnosis, prescription, treatment and remission/ recovery and more into a holistic view. A view that encompasses a human beyond just textbook definitions and classifications and that has the flexibility to accommodate unique and diverse needs of human beings.

How do we do this? It’s actually a lot more simple than you may think. Moving away from a biomedical model of health doesn’t mean nor does it require leaving behind the scientific advancements and medical processes that exist, and it doesn’t always have to mean a non-clinical approach. What it does mean is embracing the messy imperfection that is human nature and working with this instead of against it. It is in embedding the voices of those with lived experience and exploring alternate paths when things don’t go as expected.

It is in the details -calling out micro aggressions and dog whistles, being aware of the tone with which we speak, and changing the language we use. It is in seeing human brings as people over patients.