Rachael’s Story

Who am I?

A simple question, yet one that most of us cannot answer with certainty, especially those of us who fight mental health battles.

At various points throughout my 21 years, I have based my identity on an array of specific metrics and labels. My grades, my academic rank, my diagnoses, the ways I was perceived by others and the various (often demeaning) labels that they bestowed upon me all had me in a chokehold at some point or another.

Eight years ago, I would have defined myself by the grade on my latest assessment.

Six years ago, I would have defined myself by the anorexia diagnosis that I had just received.

Five years ago, I would have defined myself as a ‘lost cause’.

Two years ago, I would have defined myself as a burden to the healthcare system and by extension the world as a whole.

Now, I’m trying to discover what really makes me the person that I am.

At my core, I’m someone who is full of love and passion which I hope to share with the world. I am determined and dedicated – often to a flaw – and am unashamedly highly sensitive.

However, I am also someone who carries with me a lot of darkness.

I have known and still do intimately know deep pain. I understand how it feels to be degraded and dehumanised, to be reduced to labels and to be violated, shamed, and manipulated. I have witnessed and been subject to events more abhorrent than most people will ever know.

Not all of my life has been a battle. I had a childhood not far from those you see in Hollywood movies. I recognise and appreciate the privilege that I had receiving this and I hold eternal gratitude for the unconditional love, support and safety that was granted to me.

As I progressed from childhood into adolescence, my internal world started to erode.

I was always a very academic student. Throughout primary school I was thrust into various academic extension programs and this continued into my high school years. I was placed in a ‘Gifted and Talented’ program and learned very quickly that through strict, disciplined study rituals I could consistently achieve grades in the high nineties. It came naturally to me, and I took well to academia – where all of the world’s mysteries could be neatly summarised into chapters of a textbook. It became my mission to top all of my classes. Once I set my mind to something, I would stop at nothing to achieve it, so you best believe that is what I did. At any cost necessary.

I studied unfathomable hours with no breaks, and consistently brushed off the concerns of my parents, teachers, friends, and doctors. I fell into a pattern of neglecting all other elements of my life, including my health. I buried my head in the sand, and that sand took the form of textbooks, practice tests, assignments, and timetables.

As much as I lived in denial of the fact, I was experiencing significant deterioration in my mental health. I had exhibited symptoms of OCD since I was about 11. Sure, those around me were attuned to this, however it was mostly brushed off as the odd ‘quirk’ that comes as a part of normal, healthy development. My obsession with study was very much driven by my OCD, which itself became incredibly strong. Everything became rigid, routined, organised, planned and meticulous.

It was also around this time that my disordered relationship with food started to manifest itself in physical form. The end of 2019 and the start of 2018 was the first time that I began acting upon deeply entrenched views I had about certain foods and eating habits. Although society would have us believe that eating disorders are about image and beauty, mine very much emerged more so from ideas of morality and a need for over control.

Being so buried in my studies and continuing to excel in that domain allowed me to ignore other aspects of my life and ignore my plummeting health. My diet became increasingly restrictive, neural pathways were strengthened, and I was physically unwell.

It is vital to recognise that someone’s body composition is by no means an indicator of the severity of their eating disorder.

A person can be struggling with any eating disorder at any weight, as they are mental illnesses that take many forms. In my case though, my anorexia reared its head in a very noticeable physicality.

When it got to a stage where people could see my pain, it started to be taken seriously. I was sent off to various services and doctors and faced many knockbacks in this process. It took about a year of referrals, rejections, gaslighting, waiting lists, diagnostic checklists and appointments until I was eventually taken on as a patient a few days before my 16th birthday.

That first admission was filled with hope for me, however I was discharged into the same environment that I became ill in with little additional support and absolutely no therapy. ATAR commenced, and so did the worst year of my life. For some time I was able to keep myself physically well enough whilst drowning out all other problems and responsibilities with study. This time though, it was even more intense than before. I would time my toilet breaks and run home to ‘get more study time’. I refused to go to any appointments, events and celebrations that weren’t absolutely necessary. I was living a nightmare.

Whilst many of my peers looked at me with envy over the ‘dedication’ i displayed and my ability to achieve consistently in the high nineties, my eating – which had never truly been addressed – once again turned dire and I was sentenced to bed rest and nasogastric feeds in a hospital bed to keep my dying body alive. For some time, I was both studying absurd hours and being treated as an inpatient. I remember studying stretches of over 12 hours each day, despite the chaos that was occurring both internally and externally.

Inevitably, my doctors, parents and other supporters stepped in and I had to withdraw from ATAR – the one thing that I had dedicated my soul to. It was partly my choice, but I also knew deep down that there was no choice to be made at all. Whilst I felt an infinite pit of loss, failure and shame, I also remember indescribable relief. It was certainly a weight off my shoulders, and one which meant I could loosen my grip.

The consequence was that without study as a motivator to stay out of hospital, I fell deeper into a spiral and became a frequent flyer at my local hospital – admission, refeeding, discharge, decline, repeat.

I had all but lost hope. I saw no plausible route out of the trap in which I was stuck.

The remainder of that year and the majority of the next were a complete blur. I spent 90% of the time in a dissociative, de-realised state, fighting my brain every second of every day with no reprieve.

The extent of the mistreatment and abuse I suffered in this period is something I still can’t and likely never will fully comprehend. As an involuntary patient, doctors and nurses were well within their rights to subject me to treatments against my will and in doing so I lost a degree of my dignity. My human rights were low on the priorities hierarchy and it was a privilege to be recognised as a living, breathing, thinking and feeling form of life.

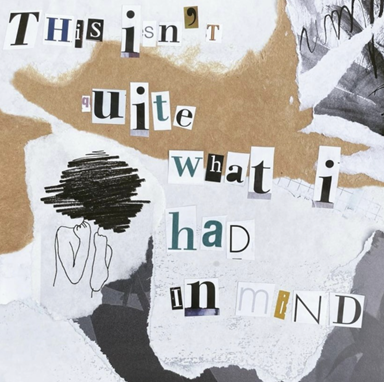

Collage by Rachael Burns

Thankfully, as do all horrific chapters, this cycle did eventually come to an end. As horrific as the treatment I experienced was, it was also a powerful motivator for me to remain well enough to avoid being sent back. It took a heck of a lot of willpower, determination and hard-work, but I did it.

I was discharged still as an involuntary patient on a Community Treatment Order (CTO), which laid out very specific criteria which I had no choice but to abide by. I was still completely under the control of my treatment team, who made it known that they could send me back to hospital with a single sheet of paper. The terms under which I could remain in the community were strict, but they were known and measurable. I became a master at appeasing my team and skating just within the boundaries.

I managed to scrape my way through weekly medical appointments for years. I kept myself just well enough to avoid hospital (although only by a very narrow margin) and convinced myself that I was living a semi-normal life. That I didn’t have a problem, or that even if I did, that it didn’t need to be addressed. I started working and this became my newest distraction into which I poured my blood, sweat and many many tears. It once again gave me something that made me feel ‘productive’ and ‘normal’ despite everything going on in my world.

I wasn’t living, I was surviving. I viewed my body as a calculator. Every action was mechanical, every word was rehearsed.

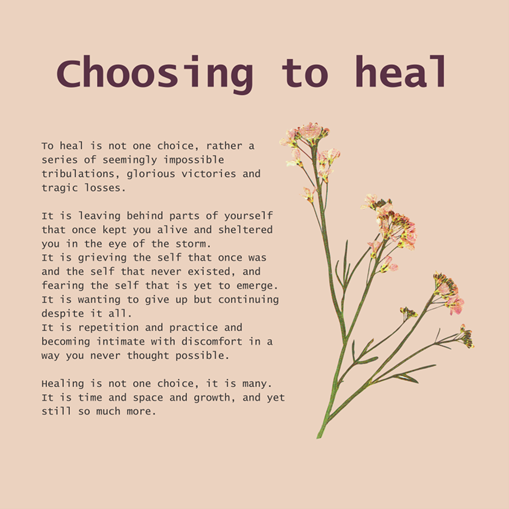

It took me at least three years of this mundane monotony to progress to a stage where I knew that change was the only path towards a life that I wanted to live.

This realisation was a very gradual shift, so much so that I didn’t even realise it was occurring. It was a culmination of exhaustion, hopelessness and frustration at my lack of change. There was no ‘lightbulb moment’, despite what the world of psychiatry and society in general may have you believe.

I started surrounding myself with others who had been in a similar situation to myself. Seeing and hearing that others had been where I was and were now on the other side of it inspired a sense of hope and built – brick by brick – the foundations of motivation for change.

There is something so sacred about the Peer space. The ability to connect over shared pain and unite in pursuit of a better future for those to come. The collective voice of justice and humanity uniting against the ocean of prejudice, bias and judgement that occupies such a large expanse of our world.

Through peers, I discovered my love for advocacy and influence. I discovered not only a reason to fight, but proof that I could endure the battle ahead. Solid, undeniable evidence that there is humanity after indignity and that there can be lightness to arise from times of complete blackout.

After years of denial, indifference, hesitation and quiet suffering, I now find myself at a place where I can envision a life that is different. I am beginning to envision a bigger picture, and am set on using my past as a tool, fighting such that my suffering was not and is not in vain.

I am in the process of pushing my own boundaries and breaking down the walls that cage me in. I am learning how to sit with distress and pull on other resources in place of behaviours that inflicted so much harm upon me.

Prose by Rachael Burns

Of course, I’m still far from where I want to be. But – for the first time – I am taking steps to get myself there.

Written by Rachael Burns

If you would like to connect with Rachael, please reach out via Linked-in or follow her Instagram account.